Mike Houston tried plexiglass barriers. He tried limiting the number of people coming into his store and reminding shoppers to maintain a six-foot distance from one another as well as employees. He ripped out all the endcaps and displays inside the Takoma Park Silver Spring Co-op in Maryland, where he works as general manager, in order to open up more space.

But the 4,500-square-foot store, which was ringing up more than 900 customers a day beginning in late February, still did not feel like a safe environment. So a week and a half ago, Houston and his management team decided to do what was once unthinkable. They closed the store.

Four days and a brand-new e-commerce platform later, the cooperative reopened as a pickup-only depot. Now, instead of walking inside the store and shopping, customers walk up to a large tent outside the store, where a worker places their prearranged order on a table, says hello and then steps away to maintain proper social distancing.

“Safety was reasons one, two and three for doing this,” Houston told Grocery Dive, noting other grocers have reached out to him about making the switch. “Even with all the procedures we put in place to make the store safer to shop, it still didn’t feel like we were doing enough.”

Grocers across the U.S. are trying to figure out how to safely serve customers amid the escalating coronavirus pandemic. They’re seeing store traffic moderate following a frenzied couple weeks, and have instituted numerous new safety steps, including erecting plexiglass barriers at checkout, marking out six-foot spacing for customers in high traffic areas and limiting the number of shoppers allowed inside stores.

But as the virus spreads, with more than 213,000 confirmed cases in the U.S. as of April 2 and many thousands more expected in the coming weeks, shoppers and employees are feeling increasingly unsafe inside grocery stores. Experts have warned shoppers to limit their trips, noting the risks that come with being in close proximity to others and touching items that others have touched. Employees at numerous stores, including Trader Joe's, Publix and Kroger locations, have tested positive for COVID-19.

With those safety concerns, many consumers are shifting their spending online. However, they often face delivery windows of a few days or more out, and no guarantee that the items they order will be in stock. Companies like Peapod and Amazon Fresh have been adding servers, updating their platforms and diligently restocking and hiring delivery drivers, but shoppers on social media continue to complain about long wait times.

Converting to dark store operations would seem to address both problems by preventing close contact while also opening up supplies to the growing number of online shoppers. In addition to a handful of independent grocers that have taken this step, Kroger last week announced it had converted a store near Cincinnati to pickup-only service.

“The pickup-only model is ideal for all customers, especially for senior and higher-risk shoppers,” said Erin Rolfes, Kroger's corporate affairs manager, in a statement.

Where could it work?

While the prospect of greater online availability and a contactless store experience might appeal to a lot of shoppers right now, going dark would only be feasible for some stores, said Neil Saunders, managing director with GlobalData Retail, including those that have multiple locations in a given area.

“I think it works in areas where you have a lot of stores and there are overlaps," he told Grocery Dive. "I don’t think any grocer wants to do it in a catchment area where they have one store. If you do that, you’re really limiting the public’s access to those stores. You’re not going to be able to fill as many orders online as you would in the traditional store model.”

Saunders said the shift could also work for individual stores in high-density urban and suburban markets where e-commerce demand is high. "As a temporary solution it makes sense, but it’s not without issues,” he said, including the complexity of reassigning staff roles and syncing up an entire store's assortment with online systems.

The need and ability to go dark also depends on the size of the store, sources said. Shoppers can travel through large stores and maintain proper social distancing, while managers can limit the number of people inside the store at one time. But inside small grocery stores, which comprise a growing number of locations in the U.S., particularly in urban markets, maintaining the recommended six-foot buffer zone in cramped aisles can be difficult, even with a limited number of shoppers inside.

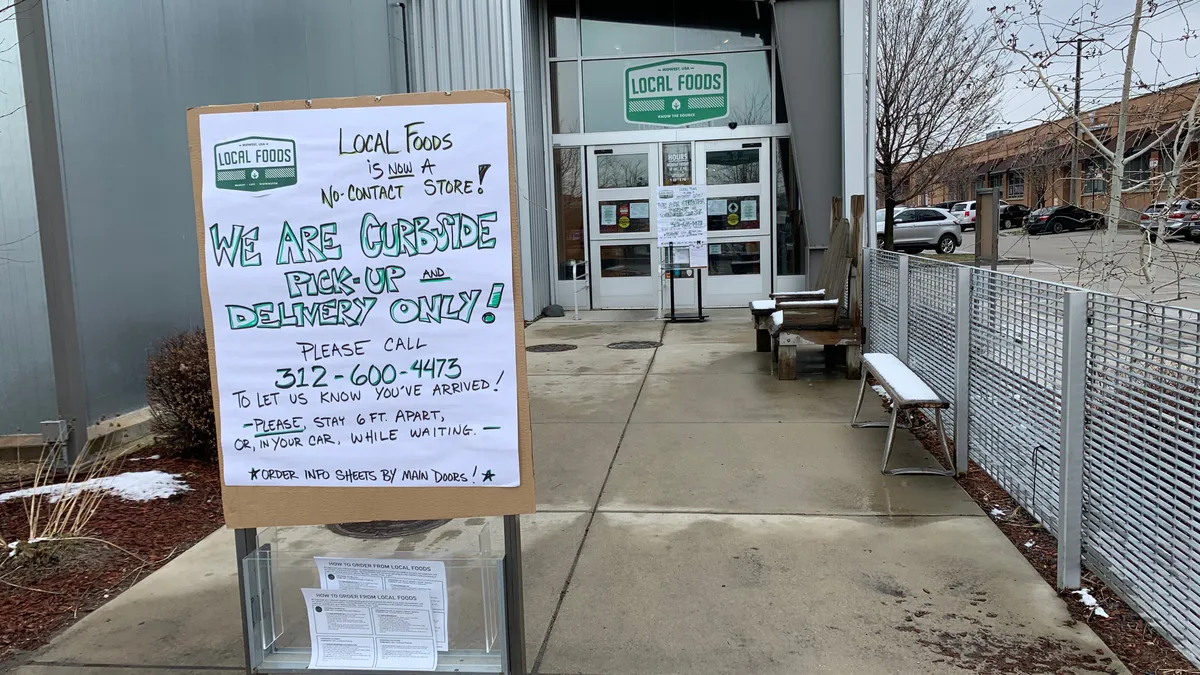

“If you’re a small footprint, you’re not in a really high-traffic area and you have a nimble enough workforce, I think you can make the switch,” Jim Carbine, CEO of Local Foods in Chicago, which converted to pickup and delivery service only at its retail location last week, told Grocery Dive.

However, moving store operations entirely online can also be operationally complex and costly. Italian Cowboy, a small specialty store in Rockland, Texas that sells wine, housewares and groceries, tried offering pickup service to customers. But the store, which serves a mostly affluent clientele on the Texas coast, struggled to fill phone orders and wasn’t able to offer the sort of high-touch service it’s known for. It also serves many older and immunocompromised customers.

Last month, owners Lowell and Deidra Rothschild decided to temporarily close the store.

“We just didn’t think we could provide an environment that was as safe as we wanted for our customers, while giving them the experience and customer service they deserve,” Lowell Rothschild told Grocery Dive.

The independent advantage

Independent grocers might be in the best position to transition, Carbine said, because they’re able to pivot quickly and often have loyal customers that will stick with them. He said Local Foods has gained new customers in recent days because shoppers know they can get a pickup slot next-day.

But those same independent grocers may struggle to quickly shift their business model and scale up their e-commerce systems. Takoma Park Silver Spring Co-op, which did not previously offer online shopping, worked round-the-clock for four days adding an ordering platform to its site, including cataloguing 13,000 products individually. Right after launching on Saturday, March 28, the site crashed for four hours due to an influx of demand.

“We have a very dedicated member community. They jumped on and started placing orders right away,” Houston said.

Carbine and the team at Local Foods spent a weekend racing to add back home delivery, which it had recently discontinued, and work out a system for picking, packing and ferrying orders out to customers. In addition to online ordering, the store also takes phone and email orders, which helps less tech-savvy shoppers and offers additional customer service, but also requires a lot of back-and-forth communication.

Carbine said the decision to close to customer traffic was “very controversial” with the store’s board of directors. The location was seeing record sales, and that was helping prop up Local Foods’ struggling wholesale business, which serves many Chicago-area restaurants that have recently shuttered. That business is running at around 15% capacity, Carbine said.

“We may be making a bad economic decision, and I’ll have to live with that. But I know from a safety of the customer and employee standpoint, we made a really good decision here,” he said.

Nearly two weeks into the new operation, things are running more smoothly. Local Foods has honed its system, in which employees shop store aisles and ring up products just like regular shoppers would, then place orders in a holding area before they go out to customers. The store at first used phones by each register to take orders. Now, workers wear headsets and chat with customers while they walk the aisles.

"If you're a small footprint, you're not in a really high-traffic area and you have a nimble enough workforce, I think you can make the switch."

Jim Carbine

CEO, Local Foods

Carbine said he hasn’t laid off any of his workforce of around 50. That includes distribution employees, about half of whom now work full-time in the retail store.

“I’ve got my driver team out in the store picking orders,” Carbine said.

Takoma Park Silver Spring Co-op has also learned a lot in a few days’ time about optimizing labor and supplies. Still, the operation is a work in progress, said Houston. Nearly all of the store’s refrigerators are now used to hold customer orders. The e-commerce site is a far cry from an Amazon or Instacart experience and doesn’t yet recognize membership benefits or take SNAP payments. To accommodate shoppers who don’t want to search and scroll through the online catalog, the store offers premade bags filled with an ever-changing assortment of groceries, dairy, meat and gluten-free goods.

“I’ve been calling it the I-don’t-care-what-I-get option,” Houston said. “It’s kind of like a CSA model.”

For retailers considering transitioning over to a dark-store model, Houston advised setting a timeline for implementation, but then being ready to adjust quickly after the switch goes into place. Carbine, meanwhile, said he questioned the decision soon after he made it, since the safety benefits aren't immediately clear, and said other managers should expect to do the same. He said it's important the decision has broad support across company stakeholders because of how quickly and decisively companies need to move.

"If you've got discord in your building and you can't get everyone on board with this decision, I think you're going to fail," Carbine said.

Looking ahead, Houston sees reasons for optimism, including a growing number of orders coming in as existing shoppers get used to the system and new customers get wind of it. The store services fewer customers than it did when the doors were open, with a little more than 300 daily orders on average. But the basket sizes are much larger, ranging from $20 up to $500. In the coming weeks, Houston plans to add a few categories online that he initially held back, like beer, wine and bulk goods.

Houston said closing the store was particularly tough given how intimately its members are connected to it. A recent survey the store conducted found that more than half of its members visited more than once a week.

“It was really emotionally hard to close the store,” Houston told Grocery Dive. “I stand by that decision, but that doesn’t make it easy.”