Pardon the Disruption is a column that looks at the forces shaping food retail.

Instacart has a history of finding a way to succeed against seemingly long odds.

It built a business around the once-crazy idea of sending people into grocery stores to shop for other people. When Amazon acquired Instacart’s largest customer, Whole Foods, in 2017, Instacart ended up translating retailer anxiety over the deal into a colossal success.

During the early days of the pandemic, it rode a tsunami of demand and added millions of customers to its rolls. Then, when it looked like many retailers might break up with Instacart as they looked to build their own e-commerce capabilities, the company instead made its case as a valuable incremental demand driver.

Instacart has made a habit of turning adversity into opportunity. So when I see the company’s recent struggles, underscored last week by news that it's slashing its global workforce by 7%, I’m conditioned to think it will soon be back on top again.

After all, Instacart’s challenges right now aren’t unique. Although many consumers may think of it as an extension of a grocer, it’s a tech company, and tech companies are looking to cut costs as investors push for better profits. According to Crunchbase, tech companies laid off 191,000 workers last year.

Instacart also went public at a tough time, with online grocery demand having ebbed considerably among millions of shoppers who had returned to stores and still felt the sting of inflation. The company’s shares fell below their offering price just days after they began trading last September and have been stuck in neutral.

Online grocery demand is still growing at a fairly robust rate, which seems to bode well for Instacart. In its first two earnings calls, company executives have positioned e-grocery as still in its early days and Instacart as the ship guiding it into the future. But online grocery is only expected to increase its share of grocery spending by a little over two percentage points over the next three years, according to data from Brick Meets Click and Mercatus. That’s impressive, but it’s not the sort of rocket fuel that’s powered Instacart in recent years.

As consumers have returned to stores en masse, the industry has pivoted from talking about online grocery to talking more about omnichannel grocery. And Instacart’s business has followed suit with its pivot into new business streams that reach across both channels.

So while the company’s previous turnarounds have relied on its ability to send an army of gig workers into stores to pick and deliver products for customers, growth in the coming years will hinge on its abilities as a digital advertiser, a consumer data cruncher and a provider of in-store technology like smart carts, electronic shelf tags and deli kiosks.

This makes me doubt that another runaway success story is in the works for Instacart, though I’m certainly not betting against the company.

Can it do more than sell ads?

When it announced layoffs last week, Instacart said it would focus on its most promising business opportunities.

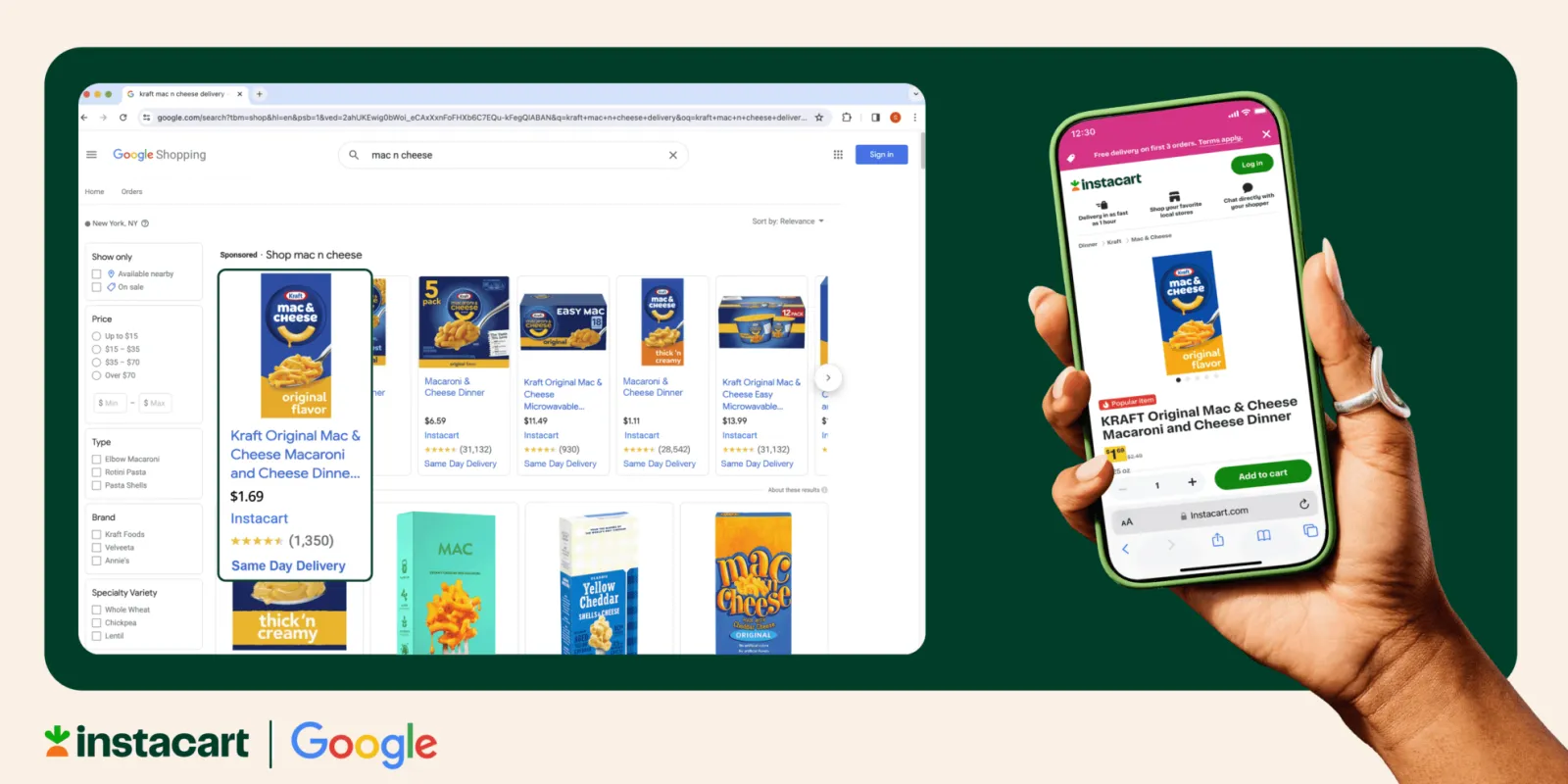

Retail media is Instacart’s strongest performer right now. Advertising and other revenue totaled $871 million in sales during its fiscal year 2023, up 18% year-over-year. In addition to CPG advertising on its own platform, Instacart also powers advertising for retailers through its Carrot Ads service and runs off-platform ads on platforms like connected TVs through partnerships with Roku, Google and other companies.

Retailers across the industry are diving into retail media, making it a hyper-competitive space. But with Instacart, CPGs seem to see an opportunity to get more bang for their buck. Just as shoppers can access multiple grocers through Instacart’s marketplace, advertisers can reach across numerous retail brands to connect with shoppers.

Instacart sees the inside of the grocery store as the next frontier for retail media. To that end, it recently rolled out ads on Caper smart carts that serve up promotions for cereal, ice cream and other goods on the their digital screen.

Advertising alone, however, can’t power Instacart through its next growth phase. It needs to innovate and grow its core e-commerce business, and it needs its shiny new enterprise solutions — including hardware like the Caper Cart, digital kiosks and electronic shelf labels — to catch on with retailers.

This is a tough proposition given how competitive all these businesses are now. DoorDash is contesting every inch of Instacart’s dominance in markets across the country. With in-store technology, Instacart was smart to acquire its way into areas like smart carts and order-ahead tech — but it’s still vying with a host of other companies also looking to bring stores into the digital future.

The in-store tech gambit will be one to watch closely. I think Instacart has a compelling vision for the future of grocery shopping. When I took a virtual tour of its “connected store” a little over a year ago, I was wowed by this vision of a place where shoppers can locate, learn about, order and pay for products using a network of digital tools — and where retailers can gather valuable data in turn. This array of offerings, to me, embodies omnichannel shopping.

But it’s not yet clear that Instacart can deliver on this promise, or that retailers and shoppers want them to. Smart carts, for instance, have struggled so far to prove they can provide a return on investment for retailers. What makes these pricey digitized carts more effective than a phone app? Generating revenue through retail media could be the answer, though I’m not sure I’d use a smart cart that bombards me with ads.

Instacart has made some promising progress with these enterprise solutions. Its pick-to-light solution, which helps shoppers locate items by lighting up a shelf beacon at the push of an app button, is now at 60 Schnucks stores, while a dozen retailers late last year added its Foodstorm deli ordering technology. Sprouts Farmers Market now uses Foodstorm’s solution across its more than 400 stores.

It will have to keep that momentum going even as it continues to compete with its partner retailers for orders and resources, which could prove quite tricky.

An evolving frenemy

Retailers’ relationship with Instacart has always been a bit awkward. The fact that a tech company controls the experience so many shoppers have with their local grocers has never sat well with those retailers.

Over time, though, grocers have come to regard Instacart as something of an annoying but reliable neighbor. They don’t seem to love Instacart piggybacking on their business, but they also don’t mind the incremental sales that its marketplace provides.

Retail media could unsettle that coexistence once again. Grocers are very eager to grow their retail media sales. And that eagerness will only grow as declining inflation and competitive headwinds continue cutting into their margins. Over the past year or so, we’ve seen regional grocers like Northeast Grocery and Giant Eagle join national players like Walmart, Amazon and Kroger in trying to lay claim to CPG advertising dollars

As Instacart’s advertising options grow, and as the company moves deeper into in-store retail media, it may vacuum up retail spending and leave retailers coming up short. As with online orders, retailers could rightly view this as monetizing off their backs, and that could negatively impact relationships with Instacart, which of course needs those same retailers to adopt its technology.

Indeed, Instacart finds itself once again in tricky frenemy territory. It wants to be a partner to retailers while simultaneously competing with them for sales.

At the same time, Instacart can’t take its eye off the core e-commerce operation that still fuels so much of its high-flying ad business. Grocery delivery is still prohibitively expensive and unappealing for a lot of shoppers. Instacart needs to find ways to bring down the cost of delivery, boost its appeal and ensure it's situated at the cutting edge of fulfillment. Most grocers aren’t yet ready to invest in automated fulfillment or even dedicated facilities — but sending gig workers into stores to shop the aisles as a proxy for the ordering customer, which is Instacart’s legacy model, is horrendously inefficient.

Instacart also needs to keep pushing the envelope on new e-commerce experiences for customers. The company’s “Ask Instacart” generative AI tool is really cool to use. I recently asked it to develop a menu of 30-minute weeknight meals, and it came back to me with some great recipes and the ability to add everything to my cart. But when I see that the company isn’t going to replace departing Chief Architect JJ Zhuang, a driving force behind “Ask Instacart,” it makes me wonder if the company will continue to take these moonshot opportunities.

Advertising may be Instacart’s star performer right now, but it can’t rely on that business to lead it into the future. Instacart is a dominant grocery delivery company that’s trying to become a dominant grocery technology company. Will it get there? Like I said, I wouldn’t bet against it — but the road ahead doesn’t look easy